Exemplary Human Practices Projects

On this page you will find example projects on: stakeholder engagement, product assessment, ethics and philosophy, policies and practices, frameworks and tools and education, inclusivity and outreach.

Here we have listed a few exemplary past Human Practices efforts in various topic areas to demonstrate the breadth of teams’ work. We hope these examples provide useful inspiration for your own engagement with Human Practices issues; however, they should not be prescriptive. The most best Human Practices methods and focus areas for your team's project may not be like any these examples―in fact we love to see new approaches!

You can find more examples of excellent and inspiring work to build upon by checking out previous Integrated Human Practices special prize winners and nominees (here are links to the 2020 and 2019 results) and previous years’ Human Practices Hubs (here are links to the 2020 and 2019 Examples pages).

Calgary 2019 team members at canolaPALOOZA, the "agronomy event of the summer".

One of the paan vendors interviewed by RuiaMumbai 2018

Engaging with potential users, stakeholders and other experts

Teams have often focused their Human Practices efforts on identifying local challenges that their project might help solve in coordination and/or cooperation with others. In these cases, teams often engage with potential users, stakeholders and other experts to inform their project selection, design and execution.

The 2020 UNSW Australia team (Best Integrated Human Practices) wanted to address widespread coral bleaching in the nearby Great Barrier Reef. They began their project by consulting with conservation experts, then spoke to social scientists and ethicists, building an understanding of the social landscape surrounding their project. This expert engagement helped them to ask stakeholders nuanced questions about what a “good” synthetic biology solution would look like. The team identified a diverse range of stakeholders to consult, including traditional indigenous owners of the land, bioprospecting researchers, local coastal community councils, and the tourism industry. Throughout these consultations, the team carefully documented how they integrated Human Practices into many design decisions, why they deliberately prioritised certain values, and how they “closed the loop” to align their project with stakeholder needs.

The 2019 Calgary team (1st Undergrad Runner Up, Undergrad; Best Integrated Human Practices) followed a human-centered design process to solve problems in the local canola oil industry. Before beginning lab work, they spoke to regulators, farmers, and manufacturers about their idea to remove chlorophyll from canola oil. They discovered that synthetic biology could impact every stage of canola production, not just oil processing. The team expanded the scope of their project and iteratively developed solutions for chlorophyll extraction, frost prediction, and seed grading. At each iteration, they re-engaged with stakeholders and technical experts to refine their design, closing the loop and producing a far better solution than they could have with a single round of feedback.

The 2018 RuiaMumbai team (Best Integrated Human Practices) aimed to produce bacteria that could clean stains from paan, a local delicacy. The team continually developed and strengthened their approach through consultation with many experts and stakeholders. For example, they approached paan vendors and an expert to identify and target the colour-producing ingredient in paan. They also approached concerned agencies and industry to understand product criteria preferred by potential users.

The 2019 FDR-HB Peru team (Best Integrated Human Practices) exemplified an full-circle approach to Human Practices. The team met with TASA, the largest fish exporter in Peru, as a continuation of their 2018 project. They didn’t only meet with company scientists, but considered the needs of stakeholders in all parts of the fish harvesting cycle. Thinking critically about the process, the team developed a cadmium bioassay that could be used while fishers were still in their boats, ultimately saving resources throughout the fish harvest. They continually refined their project through additional meetings with TASA, and carefully documented these cycles of design and feedback.

In each of these cases, teams demonstrated great consideration and integration of stakeholder needs and concerns by documenting how/what they learned and how their project goals, design, execution and communication was changed.

The results of UPV Valencia 2018's market segmentation analysis.

The cotton value chain mapped by Tec-Chihuahua 2019

Understanding the impact and uses of potential real-world products

Some teams have examined the impact and feasibility of developing, scaling and commercializing potential real-world products resulting from their projects. These teams often use entrepreneurial methods to understand user and market needs.

The 2018 Valencia UPV team (Undergrad Grand Prize) did a market segmentation analysis for their accessible, easy-to-use biological printer, which helped them decide on a target market of bio-artists. They also used a formal methodology, called the Kano model, for gathering user feedback and ranking user preferences, eventually adapting their design by adding LEDs and creating a gorgeous visual user guide. The team carefully documented their process and results to encourage future iGEM teams to use the methodology.

The Tec-Chihuahua 2019 team (Best Supporting Entrepreneurship; Nominee for Best Integrated Human Practices) wanted to address a fungal disease that was harming local cotton crops. The team did a ton of stakeholder interviews to map out every part of the cotton value chain. They spoke to seven different cotton farmers, government agencies like the Comite Estatal de Sanidad Vegetal and industry experts, including six agronomic engineers. This helped them to decide on an irrigation-based delivery method and to develop a legal plan and risk analysis, showing how Human Practices methods can support entrepreneurship.

Other teams have explored issues of intellectual property (IP) related to their work. The 2017 Aalto-Helsinki team documented their entrepreneurship process, including writing a report on the results of their patent screen. Both the 2012 Stanford-Brown Team and the 2012 British Columbia Team made IP and patent guides for other iGEM teams hoping to better understand how the rights to their discoveries and inventions might be controlled and/or shared.

The 2019 Wageningen UR team engaging with their stakeholders up close.

Developing new philosophical and ethical insights

Other teams have used philosophy and ethics to give their HP reflections more structure and to lend clarity to complex concepts (e.g. respect, responsibility, or morality). One way to do this is to apply existing ethics frameworks or principles to a project, identifying which philosophical questions emerge and—this is the tough part—devising responses or adapting the project as needed.

The 2020 UCopenhagen team (Nominee for Best Integrated Human Practices) developed a step-by-step guide to applying casuistic moral reasoning to iGEM projects. The guide’s methods helped the team to consider moral responsibility for patient distress caused by a lack of expert help in interpreting results from their home inflammation-monitoring device. The guide was developed in collaboration with SynthEthics, an biotechnology ethics initiative started by members of the 2019 Lund and Stockholm iGEM teams.

The UCopenhagen Ethics Guide is a useful complement to the Ethics Handbook created by Technion-Israel 2017, which was developed based on expert consultation and describes how abstract moral theories, like deontology and consequentialism, can relate to iGEM projects. This handbook was used by the 2018 Groningen and Bordeaux teams in their collaborative ethical evaluations of the production of bioplastics from cellulose.

The 2019 Wageningen UR team (1st Overgrad Runner Up) connected theoretical concepts in ethics to critical considerations for their project, ultimately acknowledging that their bacteriophage therapy could not be developed as a solution to agricultural pathogens without changes to its design. Using creative tools, the team collaborated with ethicists to break down concerns about their project’s impact from farm economics to overproliferation of synthetic biology technology.

Team SCUT-FSE 2017 learning about corporate biosafety practices

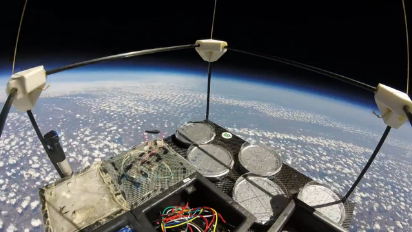

Is this stratospheric probe an “environmental release”? Team São Carlos 2019 got different answers from different regulators

Researching policies and practices

If you want to understand how the world affects your work, why not try to understand the larger real-world policy context in which you’re working? Many teams have done additional research into institutional, local, national, and international policies and practices related to their projects.

Some teams work directly with regulators. For example, EPFL 2019 (Overgrad Grand Prize) identified the regulatory chain behind crop disease reporting and diagnosis, narrowing their stakeholder groups to the farmers who call in suspected cases of crop disease, the “Phytosanitary Police” who inspect and report local cases, and the national testing authority who confirm those cases. During their project, EPFL sought the input from and were educated in the procedures of each of these stakeholders, even field testing their device while under supervision from the phytosanitary police.

Teams may find that existing regulatory frameworks do not fit their work. For example, São Carlos 2019 wanted to test their radiation resistance circuit by launching engineered bacteria into space on a stratospheric probe. However, they were unsure if this would count as an environmental release. They reached out to over 40 regulatory agencies of space and stratosphere use, and different nations gave wildly different answers about whether their work amounted to a “contained release”, and carefully documented their interviews and the ways in which existing regulatory frameworks did not fit their work. In the end, they adapted their experimental plan by launching wild-type yeast strains on the probe.

The SCUT FSE 2017 team collaborated with NPU China 2017 to analyze biosafety laws, regulations and practices in industrial settings across China, the EU and the US. The teams also analyzed the safety concerns identified by 2016 iGEM gold medal winners. SCUT FSE summarized their research and findings in a report, which they then included on their wiki.

Heidelberg’s SafetyNet software, available on their wiki

Designing (or documenting) Human Practices frameworks and tools

Many teams have developed and adapted frameworks and tools that might help other iGEMers and researchers respond to Human Practices issues that arise in their work.

Over many years, the Exeter team has shown how responsible research and innovation (RRI) frameworks developed outside of iGEM can guide excellent Human Practices work. The 2017 team, investigating bioremediation of local mining pollution, used the AREA framework (Anticipate, Reflect, Engage, Act) to contextualize their conversations with stakeholders. The 2018 team chose a project focused on Martian colonization, which had fewer direct stakeholders, so they instead followed an ELSA framework (Ethical, Legal and Social Approaches). The 2019 team (Best Integrated Human Practices, Overgrad) was a more multidisciplinary group, and so combined the AREA framework with the Engineering Design Process (EDP) cycle more familiar to the engineers and physicists on the team; that year, the team even wrote a paper based on their exploration of RRI methods.

The Heidelberg 2017 team (2nd Undergrad Runner Up; Best Integrated Human Practices) identified and addressed safety and security concerns presented by the methods of directed evolution they were using. Heidelberg not only recognized and flagged safety issues associated with their project but also went further, developing a software tool that would address both their own project’s safety challenges and those of related research. In consultation with experts in data processing and data safety, the Heidelberg team built software to scan input sequences for potential hazards. They then made their screening tool available on their team wiki so that other research teams could use and adapt it.

Members of Team Marburg learning how visually impaired students solve chemistry problems using magnetic boards

Education, inclusivity, and outreach: important work that is not usually Human Practices

Many iGEM teams have done inspiring work in public education, inclusivity, and outreach. While an important contribution to synthetic biology in general, this work does not typically lead to an interchange of ideas between the team’s synthetic biology project and society, and is thus not usually considered Human Practices.

There are exceptions to this rule. Public engagement work may lead a team to encounter new issues related to whether their project is responsible and good for the world, and responding to those issues would be considered Human Practices. For example, the 2018 Marburg team (Grand Prize, Overgrad) engaged with visually-impaired high school students, learning how many scientific concepts were expressed in an inaccessible way. As a result of this engagement, they adapted their project wiki and presentation to meet strict accessibility standards.

You can read more about the difference between Integrated Human Practices and Education in the Frequently Asked Questions.