- Human Practices

- Integrated Human Practices

Human Practices

Fast fashion - problem

The term ‘Fast fashion’ describes a business model that is making fashion trends quickly and cheaply available to consumers. It is responsible for almost 10 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions (1). Withal, this profit-orientated sector has the second largest water consumption, is responsible for ~20% of industrial water pollution from textile treatment and dyeing, contributes to ~35% of oceanic primary microplastic pollution and produces vast quantities of textile waste, much of which ends up in landfill or is burnt, including unsold product (2).

To give one example of the water consumption of the fashion industry: 20 000 liters of water are needed in order to produce one pair of jeans and one t-shirt.

Despite the awareness of the environmental and social consequences of fast fashion, the production capacity of this industry keeps increasing as well as its environmental footprint (3).

Figure 1) Estimated impact of the textile industry in 2025 compared to 2015. Displayed are CO2 emissions, water and land use. Adapted from (3).

This phenomenon can be explained by the business models Fast Fashion relies on. They instil a sense of urgency and support impulse purchases (4). For instance, Zara offers 24 new clothing collections each year, H&M offers 12 to 16 and updates them weekly. Increasing production rates, while reducing prices, product quality and product life cycle leads to an unsustainable overconsumption and waste of material, energy and resources. As a result, in 2010, textile output surpassed world population growth, a consequence of the rise of low-cost manufacturing and fast fashion (2).

Figure 2) Growth of textile production and world population from 1970 to 2020. Fibre production includes cotton, polyester, non-cotton cellulosics, polyamide and polypropylene, silk and wool. By the 2010s, textile-production growth overtook world-population growth, largely driven by the rise of cheap manufacturing and fast fashion. Adapted Figure 1 from (2).

In order for a sustainable system to arise, both production techniques and consumer attitudes must be changed. Investmenting in clean technologies and changing business models of the textile sector is as important as leading consumers to change their purchasing habits (2).

Fast fashion solution

Textile production needs fundamental changes including changes in business models, policies, introducing new sustainable practices and, a more challenging one - change in consumer behavior. Various examples to move the exploitative business more towards sustainability are emerging: some companies start to produce and craft limiting resource consumption or to manufacture at a local scale (5). Others offer jobs for reintegration or reemployment purposes (6). Some even offer services of textile maintenance. We understand that we cannot solve the problem of fast fashion at once. However, we decided to tackle what we believe is a central problem issue in this industry: textile dyeing. We studied one of the most consumed dyes in the textile sector and tried to make its production and use more sustainable while including communities in this process Our project evolve a lot while learning and receiving feedback from experts and stakeholders (see the Integrated Human Practices).

Indigo

Indigo is the oldest and one of the most consumed dyes in the textile sector. It has an intense dark blue color and is nowadays widely used for the dyeing of denim clothes (7). Despite its large number of advantages, indigo has several environmental drawbacks. About 15% of indigo used in the dyeing process is discharged to wastewater treatment plants, sometimes even into rivers, in countries where regulations are not strictly applied (8). Most of the indigo is currently produced by chemical synthesis and its production process therefore requires large amounts of chemicals The organic synthesis of indigo was introduced in 1925 by BASF based on work by Baeyer and is still in use today (9).

Figure 3) Organic synthesis pathway from aniline to indigo. Adapted from (9).

In this process aniline - a famous petroleum derivative is used as well as

dangerous chemicals - formaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide, and sodium amide. Large amount of

solvent is also used (7).

The issue of sustainability is clear with synthetic indigo. As an alternative, indigo

can be also produced with plants or bacteria. But is natural indigo more sustainable?

To answer this question, we went to Bordeaux to visit a craftsman for the production of natural indigo.

Learn more about this journey by clicking this link to our Integrated Human Practices page. Within fast

Fashion, we identified the production of indigo and the process of dyeing textile with it as a problem.

Our goal was to suggest an alternative solution. By engineering bacteria to produce indigo, we aimed to

create a new method of textile indigo-dyeing. No chemicals or petroleum derivatives are required during

the entire process.

Integrated Human Practices

Overview

This page will take you through our journey to reach our goal

described on the Human Practices page. Here, we explain how the people we interviewed,

the research we read and the experiments we conducted influenced the development

of our project.

The project started with the idea of locally producing pigments with minicells,

for increased biosafety. The pigments were to be used to produce paint of all

kinds. First, we interviewed professionals of pigment bioproduction to gain precision

on our goal. We contacted Colorifix, the first French company to develop a process

from the production of pigments to their fixation on textiles based on synthetic

biology.

We left the meeting with four main questions:

Specific application

We identified the pigment indigo as a pigment easily producible in bacteria

with the insertion of a single gene. Indigo is one of the most produced pigments in the

world. It has an important impact on the world and possesses great history (Philippe Roaldès).

Like Colorifix, choosing to dye textile with minicell-produced indigo would be a statement in

itself (Dominique Robert). It would in fact communicate our values (James Auger) against the

consequences of Fast Fashion by taking a symbol of industrial textile dyeing and turning it

into a symbol of sustainability and safety.

=> We chose to dye the textile with the indigo pigment.

Biosafety

It was confirmed that minicells cannot be considered as living

organisms and consequently, also not as Genetically Modified Organisms

(Jean-Christophe Pagès). Therefore, we decided to emphasize the separation

of bacteria from minicells. This way, we would ensure our final product to be

free from any potentially harmful organisms and consequently increase safety.

Drew Endy suggested us to introduce a dormant phage in the genome of the bacteria

that would lyse the cell after induction. However, multiple people (Jean-Christophe

Pagès, Jean Escande) pointed out that social acceptance is difficult, even if

minicells are not GMOs, it would be difficult for society to accept anyone being

in contact with them.

=> This reinforced our choice of using minicells for indigo production.

Local production

Furthermore, as many told us, producing locally influences

constraints and functions (Philippe Roaldès, James Auger and Dominique Robert).

Producing locally opens the door for a new possibility. The project could not be

reduced to a technical achievement but could also have an educational dimension,

by introducing the public to biology, local production and the sustainability they

provide (James Auger). We chose to make this idea an important component of our

project, by planning on creating workshops around the process of dyeing textile

with bacteria. This appears in our implementation proposition. Nevertheless, local

production also brings constraints. Anyone having access to the minicells greatly

decreases safety, the potential for misuse of the machine greatly increases.

=> The questions about safety and social acceptance led us to the decision not to

leave the machine freely accessible, but to keep it within a company, in the hands

of trained staff.

The decisions that were made raise new questions to answer:

We kept having interviews to ensure we asked ourselves all the necessary technical and regulatory questions.

Then, Anaïs Vielfaure gave us a lot of insights on Fast Fashion. As we saw during our research, she reminded us that the covid pandemic had shown us another weakness of it as the international supply chains were not resilient enough to withstand the distruptions. Showing that our process allows for resilience in the supply chain while being more sustainable became a goal. She gave us examples of businesses who have chosen to review the traditional values of mass production to fight overconsumption to inspire ourselves with.

See here some impressions of Boulle School with Philippe Huyghe and our visit at Beaux-Arts:

Risks and regulations

We kept exploring and learning about the safety aspects of our project

to ensure we would not be creating anything potentially hazardous. We met with

Jean Escande and Carolina Lacome, professionals of risk management. They ensured

we asked ourselves all the important questions and not overlooked any potential

risk. Together, we identified some risks (Carolina Lacome) and regulations (Escande)

within the scope of our project, since low-risk GMOs are used at a very small scale.

At this point, we also started playing with indigo production and textile dyeing in

the lab. We developed a novel method of textile dyeing with indigo without purification

and without the use of any chemicals. Learn about this journey and our results in the

Organic Chemistry page.

A new question arose: Would natural indigo production be more sustainable and efficient?

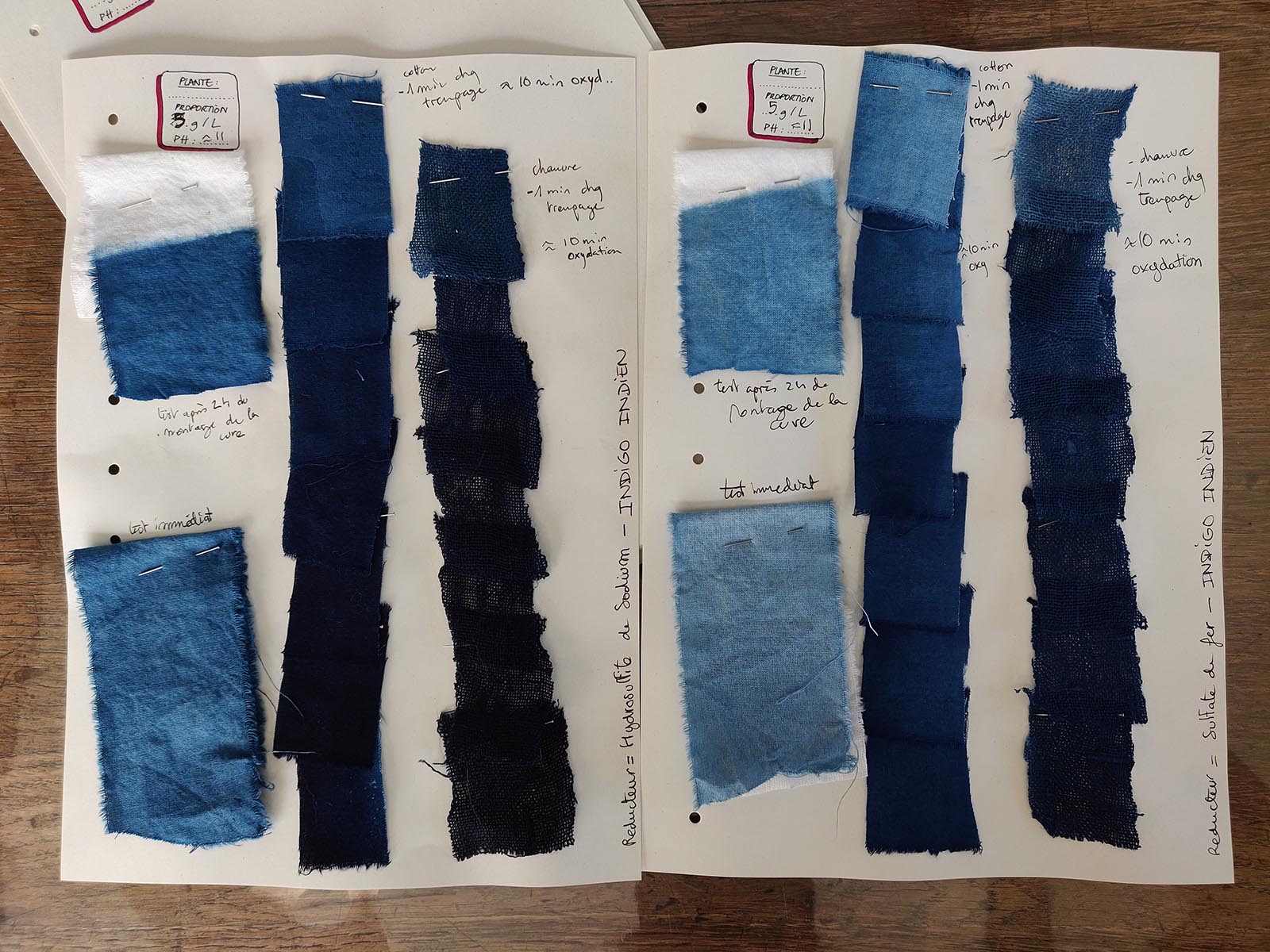

To answer this question, we participated in a textile dyeing workshop near Bordeaux (France).

It was a very complete experience, especially since we were the only participants with Caroline

Cochet, the dyeing expert. She was able to adapt the content to fit our specific questions. We

exchanged opinions about our project, her research related to indigo dye.

She taught us how to prepare a vat* of indigo with different recipes using ingredients ranging

from chemicals to fully natural ingredients. We chose to select one using sodium hydrosulfite,

and another using iron sulfate (a recipe with fructose also exists). Shades of blues were

created, from one to seven soakings, waiting for oxidation between each dipping.

Caroline also explained old and traditional ways to prepare vats, with bacteria coming from

indigo plants (that give us some idea for the future of Mini.ink!).

She was able to tell us more about the advantages and inconvenients of natural indigo production.

Its main advantage is that it does not come from petroleum and requires less chemical consumption

than chemical production. However, natural indigo, usually from India or Mexico, requires intense

laboring, often low-paid. It even used to be a slave task in the past.

See here some impressions of our workshop in Bordeaux with Caroline Cochet:

We agree with Caroline that a new method to produce indigo without these inconvenients should be created, This should be done in parallel with instilling a new way to consume and to maintain clothes.

Discussing about a project is a fundamental approach we focused on. From the beginning on, we’re bringing our attention to interviewing people related to our project. The broad spectrum of our biological process, our will to increase biosafety, our hardware, our application (dye textile) and our project allowed us to talk to a large and diverse number of people.

Portraits

Thinking about local solutions, imagining scenarios and questioning

actual biosafety, needs solid knowledge to be proposed

and to be concrete. All these following interviews helped us to

build these foundations.

Click on their names, to learn more about them and to see how they impacted our project.

Colorifix Jean-Christophe Pagès Philippe Roaldes Dominique Robert Drew Endy James Auger Philippe Huyghe Anais Vielfaure Jean Escande Caroline Cochet Carolina Lacome

*a water-insoluble dye, that is applied to a fabric in a reducing bath which converts it to a soluble form, the colour being obtained on subsequent oxidation in the fabric fibres. (Oxford Language definition)

REFERENCES

(1) United Nations Climate Change. (2018, September 6). UN Helps Fashion Industry Shift to Low Carbon. Unfccc.int. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://unfccc.int/news/un-helps-fashion-industry-shift-to-low-carbon.

(2) Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T., & Gwilt, A. (2020, April 7). The environmental price of Fast Fashion. Nature News. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s43017-020-0039-9.

(3) Remy, N., Speelman, E., & Swartz, S. (2016, October). Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula. McKinsey&Company.

(4) Anguelov, N. The Dirty Side of the Garment Industry: Fast Fashion and its Negative Impact on Environment and Society (CRC, Taylor & Francis, 2015). This book provides a good background to understanding the many problems behind industrial and global fashion manufacturing.

(5) https://www.1083.fr/, accessed: 20.10.2021

(6) https://lafabriquenomade.com/partenariat-le-slip-francais/, accessed: 20.10.2021

(7) Stasiak, N., Kukula-Koch, W., & Głowniak, K. (04 2014). Modern industrial and pharmacological applications of indigo dye and its derivatives - A review. Acta poloniae pharmaceutica,71.

(8) )Buscio, V., Crespi, M., & Gutiérrez-Bouzán, C. (2015). Sustainable dyeing of denim using indigo dye recovered with polyvinylidene difluoride ultrafiltration membranes. In Journal of Cleaner Production (Vol. 91, pp. 201–207). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.016

(9) The history of indigo. https://www.unb.ca/fredericton/science/_assets/documents/chemistry/indigo.pdf, accessed: 20.10.2021