Proposed Implementation

1. Current conservation efforts

How will our engineered microbes benefit the conservation of amphibian species across the globe? How is our approach distinguished from other approaches? We tried to answer these questions in this section.

First, by reviewing a comprehensive article on conservation of Atelopus species, we gained understanding of the current conservation status and conservation plans for the next couple of decades. Then, we examined the results of two conventional probiotic Bd mitigation approaches to assess the potential and limitations. The two activities mentioned above allowed us to better envision the context in which our microbes would be used and how our microbes could potentially provide a breakthrough for the status quo.

Since there are over 8000 known amphibians species, we had to focus on a specific group of amphibians. We centered our focus on Atelopus species since our initial inspiration for this project came from the decline of the Panamian golden toads(Atelopus zeteki). Atelopus are a genera of toads comprised of around 100 species found throughout Central and South America. They are given the name “Harlequin toads” due to their colorful appearances. Being such a diverse group of amphibians, many species of Atelopus are microendemic; occupying an extremely small geographic range with small populations. This nature makes them especially vulnerable for threats such as chytridomycosis(1). Currently among the 94 species evaluated by the IUCN, 15% are endangered, 65% are critically endangered and 4% are declared extinct(2). Their bleak conservation status deserves more attention from the global community and coordinated conservation efforts are demanded.

In the article “Harlequin Toad (Atelopus) Conservation Action Plan (2021-2041)”, the following five agendas are prioritized(1).

- Produce baseline knowledge: Gathering information about population status, natural history and threats

- Ensure viable populations in natural habitats: Developing strategies and protocols to ensure the viability of stable natural populations.

- Maintain and manage captive survival-assurance colonies: maintenance of stable captive populations, implementing reintroduction programs and monitoring efforts post-release.

- Increase visibility of Atelopus: Raising public awareness.

- Create mechanisms for multi-stakeholder collaboration and participation: Collaborating with key sectors of the private and public.

Among these agendas, the second and the third are worth noting in detail since they are relevant to our project. Action plans for the second agenda, includes “2.3.1 Evaluate the effectiveness and feasibility if commercial fungicides in mitigating Bd in Atelopus”. Specific activities for this subcategory include compiling list of fungicides for potential usage and experimenting the effectiveness of fungicides against Bd, but the article doesn’t mention how these fungicides would be used after the experimenting stage. It is unclear whether fungicides would be used only in captive breeding aquariums or would also be used in patches of land to create Bd free environments. If the latter is true, the broad specificity of fungicides is concerning since it could harm non target fungi species. We hope later versions of this article to clarify how the fungicides would be used.

Another action plan for the second agenda is “2.3.2 identify natural biological agents to control Bd in Atelopus” which includes compiling, obtaining and testing Bd inhibiting microbes. But, like the previous action plan, there is no mention on how the microbes will be used after they have been characterized for bd inhibitory activities.

The third agenda is mainly about captive breeding and reintroduction efforts. In action plan “3.4.2 Implement reintroduction programs for priority species when … the risks of emerging disease [are] mitigated”, notes the fact that the pathogens in the environment must be controlled before the release of captive bred amphibians. As long as the pathogens are present in their natural environments, reintroduction efforts are likely to fail. In this case, reintroduction efforts will be limited to areas that are uncontaminated of Bd or removed of Bd which are very difficult to acquire.

So far, we analyzed the action plans and found areas that requires improvement. We think that the use of our microbes could be a potential solution. If our microbes are applied on the toad’s skin prior to reintroduction, it could confer the toads some resistance against the pathogen. This will greatly expand the possible reintroduction sites; not only limited to Bd free areas but also including areas that have been taken over by Bd. Also, since violacein is a antifungal chemical produced from J. lividium, a microbe naturally found on the skin of amphibians, our project in line with to the later stages of action plan 2.3.2.(identification, isolation and experimentation of natural Bd resistant microbes). Lastly, the concerns for action plan 2.3.1(use of fungicides) would also be resolved since it is not necessary to use fungicides if the amphibians can survive in Bd existing environments.

References:

- Valencia, L.M. and Fonte, L.F.M. 2021. Harlequin Toad (Atelopus) Conservation Action Plan (2021-2041). Atelopus Survival Initiative, 52 pp.

- IUCN 2021. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2021-1. https://www.iucnredlist. org. Downloaded on 9 August 2021.

2. Conventional probiotic approaches

We investigated the Conventional Probiotic Approaches to get an idea of our implemantation. In conventional probiotic approaches, the bacteria that play an important role here are Janthinobacterium lividum, which survives in aerobic environments, is soil-dwelling bacteria, and is G (-) bacteria. In addition, because it produces violacein, it has anti-fungal properties for Batrachytrium dendrobatidis, a fungi that works fatal to amphibians. Therefore, we looked at the paper that confirmed the anti-fungal effect by applying J. lividum to frog skin. The frogs that examined the anti-fungal effect were Rana muscosa and Atelopus zeteki

Figure 1. R. muscosa Reference: Rana muscosa, Author: Eugene van der Pijll, Date: 2005-12-17 https://ceb.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rana_muscosa#/media/Payl:Rana_muscosa.jpg

Figure 2. A. zeteki Reference: The Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki) is a critically endangered toad which is endemic to Panama, Author: Brian Gratwicke, Date: 2008-08-02, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panamanian_golden_frog#/media/File:Atelopus_zeteki1.jpg

What's interesting here is that the anti-fungal effect of J. lividum was different for each frog species. R. muscosa obtained the resistance of Bd through J. lividum treatment, but A. zeteki did not obtain the resistance of Bd.

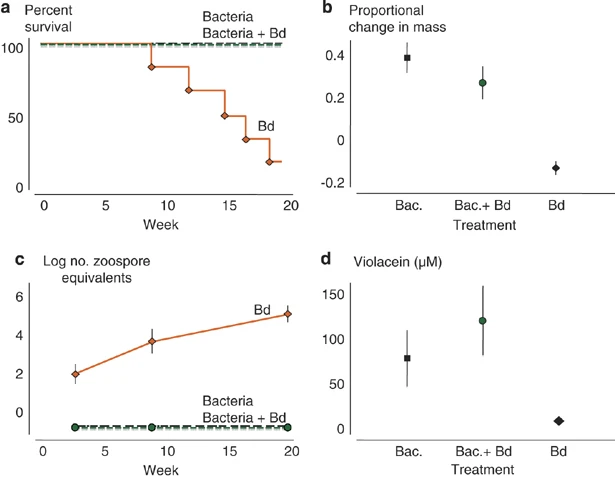

Figure 3. The results of R. muscosa (a) Survival of frog (b) Proportional change in mass (c)Log no. zoospore equivalents (d) concentration of Violacein(nM)

Figure 4. The results of A. zeteki (a) Survival of frog (b) Cell no.(Bd, Bacteria) on the skins of frogs (c)Bd infection intensity

Each result shows a significant change after treatment in the case of R. muscosa, but A. zeteki shows only a slight decrease in Bd, and eventually Frog dies.

The article suggests few possible reasons for the different outcomes between R. musosa and A. zeteki.

The first is that A. zeteki's skin might not suitable for J. lividum to survive. A. zeteki secretes several skin toxins, which are anti-bacterial materials and can affect the growth of bacteria.

The second is Different evolutionary histories of the host and symbiont. R. muscosa and J. lividum have long evolutionary histories of the host and symbiont to find symbiosis with each other in nature, but A. zeteki and J. lividum have not found such symbiosis. What we need to supplement through the previous problem is that our strain are also bacteria, so we need to have resistance to skin toxins, and we need to devise a way to combine bacteria through the common part of frog skin to prevent differences in behavior according to evolutionary history of the host and symbol.

Since J.lividium has failed to establish on the skin of A.zeteki, there is a need for an improved probiotic approach.

Reference

- Reid N Harris, Matthew H Becker et al.,"Skin microbes on frogs prevent morbidity and mortality caused by a lethal skin fungus", The ISME Journal, pp818-824, 2009.

- Matthew H. Becker, Reid N. Harris et al., "Towards a Better Understanding of the Use of Probiotics for Preventing Chytridiomycosis in Panamanian Golden Frogs", EcoHealth, 2012.

- Skin_microbes_on_frogs_prevent_morbidity.pdf

- Towards_a_Better_Understanding_of_the_Use_of_Probiotics_for_Preventing_Chytridomycosis_in_Panamian_Golden_frogs.pdf

3. Frog skin composition

Chytridiomycosis is a disease of amphibians caused by the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is transmitted through the skin of amphibians and has a critical effect on survival, causing rapid population decline. The skin of amphibians is very active. They can regulate respiration, moisture, and electrolytes well through the skin. It is not yet known exactly how the fungus kills amphibians, but it is known to interfere with the normal functioning of the amphibians' skin, causing death.

Our team plans to study focuses on the frogs of amphibians. Frog skin consists of epidermal and dermal layers. Each layer is mainly composed of epithelial and fibroblasts cells. The epidermal layer consists of stratum germinativum, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum, and the mucosal layer exists at the outermost part of the epidermis.(1)

Stratum germinativum is the innermost layer of the epidermis, composed of mitotically proliferating keratinocytes, melanocytes (pigment-producing), Langerhans cells (involved in immunity) and Merkel cells (tactile receptors). It actively divides to provide new cells for skin loss due to normal exfoliation and provides Keratinocytes to the stratum spinosum, which migrate to the stratum corneum, the uppermost layer of the skin.

Stratum spinosum comprised of distinctive keratinocytes (called prickle cells). Fibrillary proteins required for desmosome formation are synthesized and keratinization begins in this layer.

Stratum granulosum consists of granular keratinocytes migrated from the stratum spinosum. These keratinocytes contain keratohyalin granules that aid in the binding of keratin filaments and also have lamellar bodies filled with lipids. These keratinocytes secrete them as they migrate from stratum spinosum to the upper layers of the epidermis. At the same time, when they reach the stratum corneum, they lose their nuclei and organelles and become corneocytes.

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis, which is composed of keratinocytes and is responsible for most of the skin's protective barrier function. The stratum corneum has 10 to 30 corneocytes layers and has a thickness of 10 to 40 μm. Keratinocytes are filled with keratin protein to become corneocytes, and corneocytes hold each other through corneodesmosomes.

The outermost mucosal layer consists of mucus, and mucus contains microbial-community factors such as antibodies, AMPs, and lysozymes.

Reference

- Joseph F.A. Varga, Maxwell P. Bui-Marinos et al., “Frog Skin Innate Immune Defences: Sensing and Surviving Pathogens”, Front. Immunol., 2019

4. The phylogeny of mucin of different species

figure1. Image source: Tiange Lang, Sofia Klasson, Erik Larsson, Malin E. V. Johansson, Gunnar C. Hansson, Tore Samuelsson, Searching the Evolutionary Origin of Epithelial Mucus Protein Components—Mucins and FCGBP, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 33, Issue 8, August 2016, Pages 1921–1936, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw066 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The tree above includes Muc19 and confirms a previous report that Muc19 is related to the fish spiggin protein (Kawahara and Nishida 2007). It is also obvious from the analysis that Muc19 is present in fishes, amphibians, and mammals, but seems to have been lost in birds. The turtle Ch. picta and the lizard An. carolinensis show evidence of a Muc19 gene. However, in the chicken and zebrafinch the Muc19 gene is missing, providing further evidence of the lack of Muc19 in birds. As a rule Muc19 proteins contain a PTS domain, but apparently there are exceptions, like in X. tropicalis. Some of the spiggins are also different from mammalian Muc19 in that they have a PTS domain together with a fourth VWD domain

figure2 Image source: Tiange Lang, Sofia Klasson, Erik Larsson, Malin E. V. Johansson, Gunnar C. Hansson, Tore Samuelsson, Searching the Evolutionary Origin of Epithelial Mucus Protein Components—Mucins and FCGBP, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 33, Issue 8, August 2016, Pages 1921–1936, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw066 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Analysis of publically available RNA-Seq data (Necsulea et al. 2014 and other studies) indicates that the 26 different X. tropicalis mucin genes are expressed in one or more tissues (fig. 4A), suggesting that they are not pseudogenes or the result of misprediction. A number of RNA-Seq samples allowed us to specifically monitor the expression of mucins during embryonic development (Tan et al. 2013). The transcription of a number of mucins is initiated at a specific developmental stage (fig. 4B). For instance, Muc2D appears at stage 11, Muc5J at stage 15, whereas Muc2H, Muc5B, and Muc5H appear relatively late during development. Finally, the Muc2A gene is expressed throughout development, beginning already in the 2-cell stage.

5. Bd infection process and pathology

Exposure to Bd occurs when the defense mechanisms of the epidermis (AMP, bacteria, etc.) are insufficient. Zoospore penetrates the mucus layer, and zoosporangia developing occurs in the deeper host cell skin layer.

Bd has an endobiotic cycle and an epibiotic cycle.(1)(2) In the endobiotic cycle, fungus enters the skin and causes serious problems. When Bd contacts with the amphibian epidermis, the zoospore creates a germ tube that penetrates the host cell membrane. The distal end of the germinal tube is enlarged and the chytrid talus and sporangium are created in the cell. Repeat this process, digging into the deeper layers of the amphibian's epidermis. After full penetration, immature sporangia is transported to the skin surface. When the sporangia matures, the discharge tube releases the mature zoospore to the outside, causing new infections. (3)(4)

Reference

- Génesis L. Romero-Zambrano, Stalin A. Bermúdez-Puga et al., “Amphibian chytridiomycosis, a lethal pandemic disease caused by the killer fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis: New approaches to host defense mechanisms and techniques for detection and monitoring”, Bionatura, 2021

- Van Rooij, P., Martel, A., Haesebrouck, F. et al., “Amphibian chytridiomycosis: a review with focus on fungus-host interactions”, Vet Res 46, 137 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-015-0266-0

- Lee Berger, Rick Speare et al., “Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1998

- Laura F. Grogan, Jacques Robert et al., “Review of the Amphibian Immune Response to Chytridiomycosis, and Future Directions”, Front. Immunol., 2018

- Flechas, Sandra V et al. “The effect of captivity on the skin microbial symbionts in three Atelopus species from the lowlands of Colombia and Ecuador.” PeerJ vol. 5 e3594. 31 Jul. 2017, doi:10.7717/peerj.3594

Possible improvements

Bacterial species were isolated from the skin of three Atelopus speceis, _A. elegans, _A. aff. limosus, and _A. spurrelli, by Flechas, Sandra V et al.(5) For A. elegans-C(captive), bacterial species of their skin included Massilia, Novosphingobium, Microbacterium, and etc, while A. elegans-W(wild) skin had Rhizobium, Caulobacter, and so on. In A. aff. limosus-C, several bacteria including Listeria and bacillus were discovered. Pseudomonas were found in all species in common. Also, they had common bacterial species such as Acinetobacter(except A. elegans-W), Chryseobacterium(except A. elegans), Comamonas(except A. elegans-W), and Stenotrophomonas(except A. elegans-C and A. aff. limosus-W). Though our project was developed in an E.coli chassis due to the ease of manipulation, it would be the best if our systems could be included in species mentioned above since they share a long evolutionary relationship with the host.