1. Light dependent Violacein production

Violacein

The bisindole alkaloid violacein is a natural bluepurple pigment isolated from Gram-negative bacteria. The violacein is an indole derived violet pigmented compound and a promising agent with following biological activities: antibacterial antifungal, antiprotozoan, and anticancer. These biological and pharmacological activities of violacein have made it attractive for biotechnology research. It's known that increasing concentrations of violacein reduced Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis growth(1). Several terrestrial and marine gram-negative bacteria were known to produce violacein including Chromobacterium violaceum, Janthionobacterium lividum and 7 other genus(1). Violacein is formed by enzymatic condensation of two tryptophan molecules, requiring the action of five proteins(2). The genes required for its production, vioABCDE, and the regulatory mechanisms employed have been studied within a small number of violacein-producing strains. In Massilia genus, three strains have been reported as producing violacein and recently, the complete genome of Massilia sp. strain NR 4-1 as well as five key enzymes of the violacein biosynthesis has reported(3). Recent study sought to engineer E. coli and its metabolic pathways to improve the violacein yields. For this, the authors overexpressed the genes related to tryptophan production and knocked out several genes and pathways which would detract the carbon flux away from this amino acid(4). The engineered E. coli strain, TRP11, produces about 20 𝜇mol tryptophan per gram DCW (gDCW). By comparison, the control wild-type strain only produced about 0.3 𝜇mol tryptophan/gDCW, representing an increase in the tryptophan concentration of more the 60-fold. They next introduced the vioD gene into the chromosome of this strain and a plasmid expressing the vioABCE genes(5). Performing fed batch fermentations over a 12-day period with this strain, which they designated as Vio-4, they were able to generate 710 mg/L violacein at more than 99% purity, demonstrating that E. coli can be used to produce high level concentrations of this bisindole specifically(6).

References

- Brucker, Robert M., et al. “Amphibian Chemical Defense: Antifungal Metabolites of the Microsymbiont Janthinobacterium Lividum on the Salamander Plethodon Cinereus.” Journal of Chemical Ecology, vol. 34, no. 11, 2008, pp. 1422–1429., doi:10.1007/s10886-008-9555-7.

- Verbrugghe, Elin, et al. “Growth Regulation in Amphibian Pathogenic CHYTRID Fungi by the Quorum Sensing Metabolite Tryptophol.” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 9, 2019, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03277.

- Myeong, Nu Ri, et al. (2016). "Complete genome sequence of antibiotic and anticancer agent violacein producing Massilia sp. Strain NR 4-1". Journal of Biotechnology. 223: 36–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.02.027

- Choi, S.Y., et al. (2015). Violacein: properties and production of a versatile bacterial pigment. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 465056.

- Haisheng Wang, et al. (2012). Biosynthesis and characterization of violacein, deoxyviolacein and oxyviolacein in heterologous host, and their antimicrobial activities

- Seong Yeol Choi, et al. (2015). Violacein: Properties and Production of a Versatile Bacterial Pigment, Hindawi

AND gate

Why use an AND gate?

We want to produce violacein when frogs are exposed to chytridium in several conditions. Therefore, AND gate was used to produce violacein when frogs were exposed to these two conditions-normal activity->blue light, exposure to chytridium->chitin detection-corresponding.The first input uses the substance produced when detecting chytridium and then the supD tRNA produced from the previous input is available when exposed to blue light, so we can produce violacein only under the conditions we want.

T7 polymerase AND gate (BBa_K568004)

We chose the promoter that is regulated by the YcgF/E system as blue light sensor. The domains YcgE and YcgF are endogenously present in Escherichia coli are thought to regulate the biofilm formation when E.coli is exposed in an aquatic environment. Blue light induces the dimerization of YcgF that then directly binds to the repressor YcgE and releases the repressor from the operator. The expression of YcgE and YcgF and therefore as well the expression of the controlled gene is increased at low temperature(11). The AND gate (BBa_K568004) uses the blue light sensor as a promoter and then transcribe the T7ptag. Since T7ptag is translation only through supD tRNA, we can make AND gate work through blue light and input we set if designed to be expressed using T7 polymerase through the desired input. However, the size of the parts is too large, especially if combined with the violacein genes, the expected size would be 15 kb, which would not be suitable for transform, so we looked for another way.

Split vio operon AND gate

References

- http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K568004

- https://2011.igem.org/Team:TU_Munich/project/introduction

The light sensors

To prevent cells from distrupting soil ecosystems by producing violacein under soil, we decided to use light as one of the inputs that induce violacein production. Below are some light sensing systems we considered during the design process.

YF1

Figure 1. YF1(PDB ID: 4GCZ)(1)

YF1 is a protein with a Lov domain which bind a FMN, so blue light can be detected. Also, YF1 has a kinase site, so can phosphorylate other proteins. However, when YF1 is exposed to blue light, YF1 do not phosphorylate other proteins due to conformation change of YF1. In this figure, Lov domain is the Red and Blue section and FMN is the Yellow section. If YF1 is not exposed to blue light, FixJ may be phosphorylated. The FixJ phosphorylation is performed by ADP represented by green and 161 histidine represented by Magenta, that is kinase site(2).

Figure 2. YF1 phosphorylating FixJ when there is no light(3)

Figure 3. YF1 exposed to blue light (3)

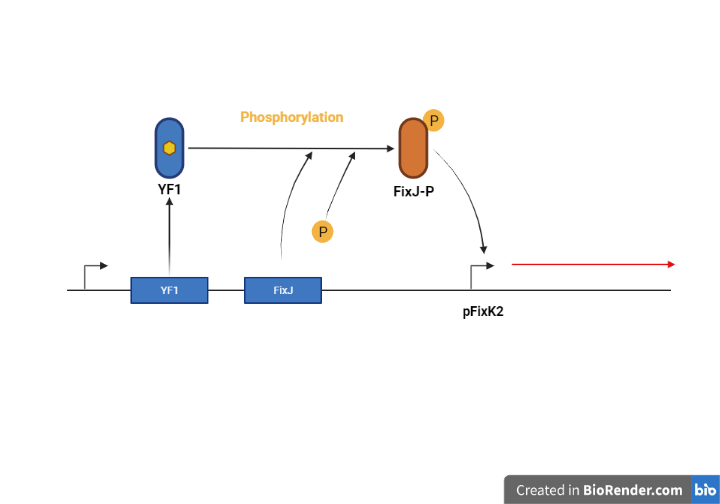

pDawn

We used the plasmid pDawn, which uses a blue light photoreceptor, to allow the expression of light-inducing genes when bacteria are exposed to light. Plasmid pDawn was created by inserting a cI inverter in pDusk as shown in the figure below. Insertion of the λ phage repressor cI and the λ promoter pR in pDawn inverts the the system to be light activated. YF1 has a blue light sensor domain, and in the absence of light, YF1 phosphorylates FixJ which activcates pFixK2. pDawn has a relatively higher dynamic range and lower background expression, and does not require additional components such as genes that encode enzymes for chromophore synthesis or incorporation(4). And it can be adjusted by time and light intensity changes, making it suitable for automation, optimizing yield and purity. So we decided that pDawn was a good fit for this project.

References

- https://www.rcsb.org/structure/4GCZ

- Oskar Berntsson et al., "Sequential conformational transitions and α-helical supercoiling regulate a sensor histidine kinase", Nature communication 8(1), 2017, pp1-8.

- http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1065310

- Ohlendorf, Robert et al., "From dusk till dawn: one-plasmid systems for light-regulated gene expression." Journal of molecular biology 416.4 (2012): 534-542.

2. Mucus binding domain surface display

Mub

To minimize the engineered cells from detaching and leaking out to the environment after inoculation, we had to increase the cells’ adherence to the outermost mucus layer of the amphibians’ skin. Therefore, we decided to display mucus binding domains on the outer membrane of the cells. While in search for mucus binding domains, we found that a lactobacillus strain(L. reuteri 1063) possessed adherence properties to intestinal mucus. However, since lactobacillus bacteria are gram-positive, we needed to use a different mechanism to display the domains on the outer-membrane of our gram-negative chassis. A well-known surface display protein OmpA was chosen as our means to display the mucus binding domains. From various candidates of proteins involved in mucus binding (1), we chose Mub2 for surface display. The identification and initial characterization of these protein domains were done by Roos and Jonsson(2). lambda phage libraries were created from L.reuteri 1063’s DNA and the protein of interest was subsequently selected and identified. The protein contains a N terminal signal sequence, C teriminal LPTG anchoring motif, 6 Mub1 repeats(RI-RVI) and 8 Mub2 repeats(R1-R8). Both types of domains exhibited adhesive properties to pig gastric mucin.

Another research by MacKenzie et. al (3). highlights the role of this domain in binding to mucus by revealing that L. reuteri strains with mucus adhesive properties possess and express Mub domains. Crystal structure of the Mub2 domain was revealed by MacKenzie et. al(4). The domain is composed of two structurally similar subdomains: the N-terminal domain(B1) with a ubiquitin like beta-grasp fold, and the C terminal domain(B2) with a non-canonical version without an alpha helix.

Since Mub1,2 domains were better characterized, we decided to fuse these domains to the C terminuas of the surface protein OmpA. We acquired the sequences of the Mub domains from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/6707063. We fused the domainas R4-7 and R4,5 Mub2 domains to the partial OmpA part(K103006) with a GS linker in between. https://benchling.com/s/seq-5WW6LSK3eFmng9Z1SK5A https://benchling.com/s/seq-YFxJHRIgGRz0RiOCh3sY The new fusion proteins are registered as parts K3837005 & K3837006.

References

- Juge N. Microbial adhesins to gastrointestinal mucus. Trends Microbiol. 2012 Jan;20(1):30-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.10.001. Epub 2011 Nov 14. PMID: 22088901.

- Roos S, Jonsson H. A high-molecular-mass cell-surface protein from Lactobacillus reuteri 1063 adheres to mucus components. Microbiology (Reading). 2002 Feb;148(Pt 2):433-442. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-2-433. PMID: 11832507.

- MacKenzie DA, Jeffers F, Parker ML, Vibert-Vallet A, Bongaerts RJ, Roos S, Walter J, Juge N. Strain-specific diversity of mucus-binding proteins in the adhesion and aggregation properties of Lactobacillus reuteri. Microbiology (Reading). 2010 Nov;156(Pt 11):3368-3378. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043265-0. Epub 2010 Sep 16. PMID: 20847011.

- MacKenzie DA, Tailford LE, Hemmings AM, Juge N. Crystal structure of a mucus-binding protein repeat reveals an unexpected functional immunoglobulin binding activity. J Biol Chem. 2009 Nov 20;284(47):32444-53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040907. Epub 2009 Sep 16. PMID: 19758995; PMCID: PMC2781659.

Surface display (OmpA)

Microbial cell-surface display, or surface expression system is a method carried out by expressing a fusion protein of the desired protein or peptide and anchoring motif, which are usually cell-surface proteins or their fragments (carrier proteins). The surface expression method is used in various applications such as library screening, live vaccines, whole-cell biocatalysis, bioremediation, biosensor, and biofuel. (1)

Many surface expression methods have been developed for various strains. Among these many strains, gram-negative cells have an outer cell membrane, which impedes the surface display of proteins, but more surface expression methods were studied because of the vast amount of knowledge gathered through the study of E. coli strain. (2)

Each expression method is based on a variety of anchoring motifs, and accordingly, the passenger protein must be fused in appropriate ways. Among them, we investigated the method using autotransporter and the method using Lpp-OmpA hybrid.

Autotransporters

Autotransporters are proteins whose entire structure is displayed on the cell surface without cleavage through the Type Va Secretion method.(3) It consists of three main parts: signal sequence located in N-terminal, the passive domain, and translocator domain in C-terminal.

The N-terminal signal domain directs the synthesized polypeptide itself to periplasm through Sec apparatus.(4) The C- terminal translocator domain consists of α-helical secondary structure and β-domain that make a hydrophilic pore in the outer membrane. Through this pore, the fused internal passenger domain connected to the α-helix passes through the outer membrane and is displayed outside the cell. (1)

Various types of protein domains such as adhesin, protease, esterase, and lipase are located in the passenger domain. (2) If the passenger domain is converted into the another protein domain in interest to be displayed, the changed protein domain will be displayed on the cell surface. Since the Passenger domain is between the N-terminal signal domain and the C-terminal translocator domain, the use of autotransporter requires a sandwich fusion strategy that changes genes in between. (5)

Lpp-OmpA hybrid

Unlike autotransporter, Lpp-OmpA hybrid uses a C-terminal fusion method. (5) Lpp-OmpA hybrid consists of signal sequence, first nine N-

terminal residues of the mature E. coli lipoprotein, and the residues of the E. coli outer membrane protein A (OmpA). Lpp part is necessary for proper localization to the outer membrane, and the OmpA part is responsible for the transportation of foreign proteins fused at the C-terminus across the outer membrane.

As shown in the figure above, passenger domain can be fused into OmpA's C-terminal and transported across the outer membrane. Therefore, the C-terminal fusion strategy should be used in the Lpp-OmpA hybrid.

In 2008 iGEM, the Warsaw team synthesized the BBa_K103006 biobrick part, which consists of Lpp: Lipoprotein signal peptide, OmpA: Outer membrane protein A, linker (Gly-Ser-Gly), which enables us to attach the display domain behind the linker. (6) Using this part, our designed protein can be easily synthesized just by attaching the Mub protein domain to C-terminal. Therefore, we decided to use Lpp-OmpA hybrid system for our design.

References

- Yang, T. H., Pan, J. G., Seo, Y. S., & Rhee, J. S. (2004). Use of Pseudomonas putida EstA as an anchoring motif for display of a periplasmic enzyme on the surface of Escherichia coli. Applied and environmental microbiology, 70(12), 6968–6976. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.12.6968-6976.2004

- Gustavsson, M. (2011). Surface expression using the AIDA autotransporter: Towards live vaccines and whole-cell biocatalysis (TRITA-BIO Report 2011:25). Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm.

- Leo, J. C., Grin, I., & Linke, D. (2012). Type V secretion: mechanism(s) of autotransport through the bacterial outer membrane. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 367(1592), 1088–1101. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0208

- Sichwart, S., Tozakidis, I. E., Teese, M., & Jose, J. (2015). Maximized Autotransporter-Mediated Expression (MATE) for Surface Display and Secretion of Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia coli. Food technology and biotechnology, 53(3), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.17113/ftb.53.03.15.3802

- Bielen, A., Teparic, R., Vujaklija, D., & Mrša, V. (2014). Microbial Anchoring Systems for Cell-Surface Display of Lipolytic Enzymes. Food Technology and Biotechnology. 52. 16-34.

- http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K103006

3.Fungal pathogen detection through chitin

CadC

For pathogen detection, receptor mediated detection was necessary since it was unclear whether the pathogen associated molecules would diffuse into the cell. In search for a suitable system, we looked at previous igem projects. We found a few previous projects that included a receptor mediated detection system. Various receptor based systems were tested by previous igem teams, but the one that was the most suitable overall for our project was the CadC-pCadBA used by team Uppsala(5). Their project was based on a previous research(6) which engineered the wild type CadC receptor by fusing caffein-binding single domain antibodies(VHHs) at the periplasmic portion. Upon ligand binding, the periplasmic domain(C-terminus) dimerizes and brings together the split DNA binding domains(DBDs) in the cytosolic side(N-terminus) to express genes under the pCadBA promoter. This research further improved the design by testing different version of linkers and found that the removal of the juxtamembrane linker increased the fold change of the reporter gene expression.

CERK1, LYK5

To use the CadC system, we needed to find domain that dimerizes upon the binding of the pathogen specific ligand. This property was found in the chitin binding receptor CERK1 of A. thaliana. This Not only the whole receptor, but also just the ectodomain(ECD) showed dimerizing properties in pull down and western blotting experiments when treated with chitin(7). No dimerization was observed when peptidoglycan was treated. Crystallization data revealed the presence of 3 LysM domains in atCERK1-ECD. It also enabled the identification of key residues of atCERK1 interacting with NAG of chitin. Structure of ECD can be viewed at PDB(7)

One concern during the design process was that while the CERK1-ECD is a N terminus domain, it had to be attached to the C terminus of CadC. However, we observed that the N & C terminus of CERK1-ECD is located close to each other(9). We thought that since the two termini are closely located, it wouldn’t make much of a difference whether the connection occurs in one or another. Though our intuition needs validation, we decided to proceed with the design. We also included a flexible GS linker between CERK-ECD and CadC so that CERK1-ECD is allowed more freedom in orientation while binding to chitin. This domain will be fused at the periplasmic side of a CadC. There is a CadC-VHH biobrick (BBa_K3425100) so we replaced the VHH region with the CERK1 domain.

BBa_K3837007: AtCERK1(ECD)-CadC fusion receptor(short linker) BBa_K3837008: AtCERK1(ECD)-CadC fusion receptor(long linker)

Also, a coreceptor LYK5 was shown to facilitate the dimerization. LYK5 showed even higher binding affinity towards chitin and LYK-CERK association in the presence of chitin was stronger than the dimerizing association of CERK1 monomers. Dimerization of CERK1 was absent in LYK5 mutant protoplasts (8). However, the dimerization of LYK5s is known to occur spontaneously. This would be a problem since unwanted dimerization would yield false positives. Thus, we needed a way to disable the DBD of CadC which LYK5 is fused to. Then LYK5 will be able to assist chitin binding of CERK1 without inducing gene expression. We solved this problem by introducing a mutation in the DBD. More information in Engineering page.

BBa_K3837009:LYK5-CadC fusion receptor with disabled transcription activation activity on pCadBA(short linker) BBa_K3837010:LYK5-CadC fusion receptor with disabled transcription activation activity on pCadBA(long linker)

References

- https://2020.igem.org/Team:UofUppsala/Design

- Chang HJ, Mayonove P, Zavala A, De Visch A, Minard P, Cohen-Gonsaud M, Bonnet J. A Modular Receptor Platform To Expand the Sensing Repertoire of Bacteria. ACS Synth Biol. 2018 Jan 19;7(1):166-175. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00266. Epub 2017 Oct 30. PMID: 28946740; PMCID: PMC5880506.

- Liu T, Liu Z, Song C, Hu Y, Han Z, She J, Fan F, Wang J, Jin C, Chang J, Zhou JM, Chai J. Chitin-induced dimerization activates a plant immune receptor. Science. 2012 Jun 1;336(6085):1160-4. doi: 10.1126/science.1218867. PMID: 22654057.

- Cao Y, Liang Y, Tanaka K, Nguyen CT, Jedrzejczak RP, Joachimiak A, Stacey G. The kinase LYK5 is a major chitin receptor in Arabidopsis and forms a chitin-induced complex with related kinase CERK1. Elife. 2014 Oct 23;3:e03766. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03766. PMID: 25340959; PMCID: PMC4356144.

- Schlundt, A., Buchner, S., Janowski, R., Heydenreich, T., Heermann, R., Lassak, J., Geerlof, A., Stehle, R., Niessing, D., Jung, K., & Sattler, M. (2017). Structure-function analysis of the DNA-binding domain of a transmembrane transcriptional activator. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01031-9

4. Kill switch

To prevent the cell we designed from falling off the amphibian skin and proliferating elsewhere, we created a kill switch using the Lux gene and MazE, MazF gene so that the cells can survive only in areas with high cell density.

LuxI produces acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL). AHL can pass through the cell membrane, so the concentration of AHL increases as the number of cells increases, and this AHL and LuxR protein bind to stimulate the AHL and LuxR regulated promoters to promote cl repressor transcription. The generated cl repressor suppresses the cl regulated promoter, preventing transcription of MazF. MazE,F is a suicide system. MazF produces a stable toxin, and MazE produces an unstable antitoxin. mazF cuts a specific site of mRNA and causes apoptosis. mazE is an antitoxin against mazF, which prevents apoptosis. In our kill switch, the antitoxin, MazE, is continuously expressed, but the toxin, MazF, is regulated by Lux. When the cell is removed from the skin of the amphibian and placed in a new environment, the concentration of AHL is lowered, the transcription of the cl repressor is suppressed, and the transcription of MazF proceeds. Although MazE is continuously expressed, it is unstable, so if more mazF is produced, the apoptosis process is triggered by toxin. For continuous expression of LuxI and LuxR, we tried to use promoters J23100 and RBS B0034. However, when J23100 and B0034 were used for LuxI and LuxR, the expression level of LuxR/HSL dimer was too high when there was one cell, so another combination of promoter and RBS was found through experiments. We decided to use J23106, B0032 for LuxR and LuxI. More information on our Model page.

References

- http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2292002

- http://parts.igem.org/Lux