Design

1. Overview of in vivo self-assembled small interfering RNA delivery system

Our design idea was mainly based on the article In Vivo self-assembled small RNAs as a new generation of RNAi therapeutics. This article introduces a novel RNAi treatment and delivery method, which uses somatic cells as bio-chassis to generate siRNAs and deliver these siRNAs to desired cells through self-generated exosomes from somatic cells. (Fig.1) For example, NJU-China tried to apply it in treating none-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in iGEM 2020. The overall strategy was to transfect liver cells with DNA circuits using intravenous injection, so that the liver cells would function as a factory to produce therapeutic siRNAs and cancer-targeting peptides. It is known that almost all cell type in eukaryotic body will secrete exosomes, which carry cargo or mediate communication between cells, and liver cell is no exception. So the siRNAs and cancer-targeting peptides would be loaded in/on exosomes and would target cancer cell with the help of cancer-targeting peptide loaded on exosome membrane. After entering the cancer cells, the siRNAs would take effect and eventually kill the cancer cells.[1]

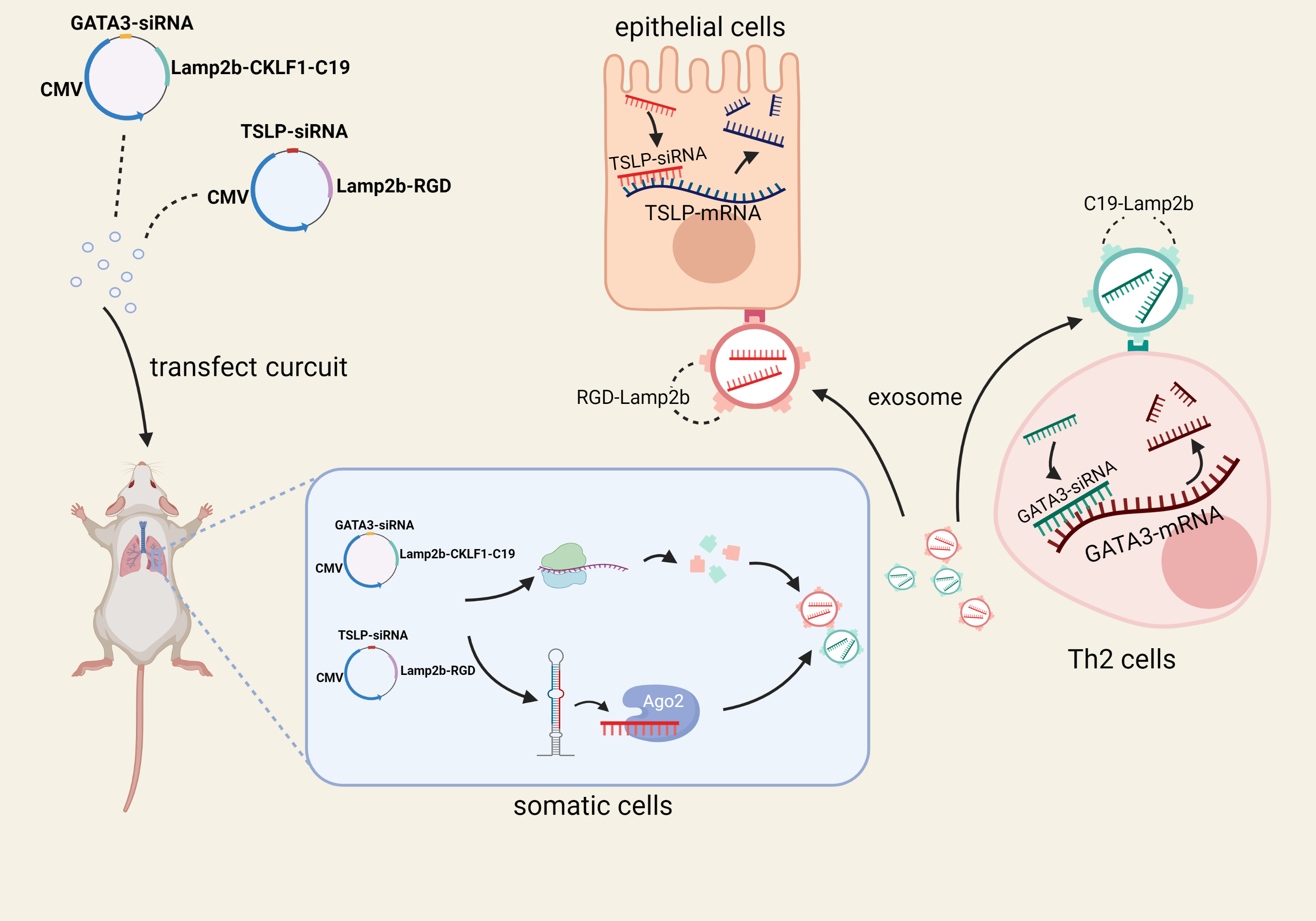

Fig.1 The in vivo self-assembled small interfering RNA delivery system described in the article In Vivo self-assembled small RNAs as a new generation of RNAi therapeutics

2. The improvements we have done

2.1 We use GATA3 and TSLP as our target genes

As we have described in Description, our team this year focus on asthma, hoping to treat it by inhibiting type 2 inflammation in asthma, since type 2 inflammation truly plays a key role in asthma development and progression. The features of type 2 inflammation, including large quantity of cytokines like IL-4, IL-5and IL-13, massive IgE secreted by activated B cells, eosinophil infiltration, etc. will eventually lead to asthma symptoms.[2]

We know that type 2 inflammation is mediated primarily by Th2 cells in the situation of allergic reaction. Activated Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, etc. which mediate eosinophil activation, B cell isotype switching and IgE synthesis, and a series of downstream reactions. So Th2 is at the center of the whole type 2 inflammatory response. Fortunately, we found that expression of the transcription factor GATA3 is essential for Th2 cell maintenance and activation.[3] Its downstream mediates the expression of a series of cytokines related to type 2 inflammatory response, including the previously mentioned IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, etc.

In addition to Th2 cells, ILC-2 cells are also involved in the development and progression of type 2 inflammation in asthma. ILC-2 cells also produce cytokines related to type 2 inflammation, such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-9, which promote the development and progression of asthma. Interestingly, ILC-2 cells are also under the control of the transcription factors GATA3 as the Th2 cells do. [4]In addition, we also found that epithelial-cell-derived TSLP can effectively activate ILC-2 cells and play a critical role in the progression of asthma.[5]

2.2 We use CKLF1-C19 and RGD as our targeting peptide

As for the Th2 cell targeting peptide, we selected CKLF1-C19 as the Th2 cell targeting peptide by targeting CCR3 on it. Apart from its targeting ability, CKLF1-C19 has been reported to reduce airway eosinophilia, lung inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma mice. [6] As a result, CKLF1-C19 will play dual role in our project: not only will it help exosomes to target Th2 cells, but also it will help reduce the symptom in asthma mice.

As for the epithelial cell targeting peptide, we selected RGD for targeting with the help of ZJU-China. RGD is a well-known targeting peptide in its ability to target integrins widely expressed on the surface of epithelial cells.

Eventually, we constructed our targeting proteins CKLF1C19-Lamp2b and RGD-Lam2b. These are fusion proteins with targeting peptide domain located on the N terminal. Detail method can be found at NJU-China Wiki in iGEM 2015.

2.3 We use nasal inhalation as administration strategy

We interviewed Professor Wu Jinhui from Institute of Drug R&D, Nanjing University. Prof. Wu suggested that regular intravenous therapy for asthma, a chronic disease that requires almost lifelong medication, would do harm to the therapy compliance. Inspired by this, after careful discussion and literature reading, we planned to administrate our DNA circuits to asthma patients by nebulization (for mice is nasal inhalation) rather than intravenous injection, for it's simpler, easier to operate, and more economical. Most importantly, nebulization allows DNA circuits to be significantly enriched in lung tissue, rather than circulating through the bloodstream like intravenous injection will do, which poses safety and ethical risks.

2.4 We use minicircle DNA as our vector

Finally, we also improved the gene vector. Because we wanted to reduce the immune response caused by the immunogenicity of the DNA circuits itself, and we wanted to prolong the expression time of the DNA circuits in the body as well. So we chose minicircle DNA (mcDNA) as our gene vector. mcDNA is a small loop DNA that devoid of the plasmid bacterial backbone and has lower immunogenicity and longer expression time in vivo than ordinary plasmid.[11] According to unpublished data from our laboratory (Fig. 2), there was a significant difference in the duration of siRNA expressed by mcDNA and its parent plasmid in serum after a single intravenous injection, indicating that mcDNA was significantly superior to the parent plasmid in the duration of effect.

Fig.2 The duration experiment of mcDNA versus its mother plasmid, data not published. Equal mass of DNA circuits expressing EGFP-siRNA was intravenously injected in mice and siRNA expression in serum was tested in day 1, 4 and 10. The result shows tremendous advantage of mcDNA in duration of effect compared with its mother plasmid.'

2.5 We use liposome to carry our DNA circuit into mice

We considered that asthma patients are very sensitive to allergens, such as smoke or viruses, so compared with commonly used gene therapy vectors, such as AAV or lentivirus, we prefered to use safer liposome to wrap and deliver our DNA circuits.

3. Our design of targeted therapy of asthma by self-assembled small interfering RNA in vivo

We constructed two mcDNAs, mcDNA-CKLF1C19-Lamp2b-GATA3-siRNA and mcDNA-RGD-Lamp2b-TSLP-siRNA which will target GATA3 in Th2 cells and TSLP in epithelial cells respectively. We will transfect mice lung epithelial cells through nasal inhalation with the above two DNA circuits carried in liposomes. It is expected that the DNA circuits will be successfully transfected into mouse lung epithelial cells, where the DNA circuits will express relevant targeting proteins and siRNAs. Then these siRNAs will be wrapped in exosomes secreted by cells afterwards, and target to the corresponding cells with the help of the targeting proteins, and finally knock down the corresponding mRNA expression in order to achieve inhibitory effect on the target genes, which will eventually control asthma symptoms.

Fig.3 Illustration of our design of of targeted therapy of asthma by self-assembled small interfering RNA in vivo

Reference:

[1]Fu Z, Zhang X, Zhou X, et al. In vivo self-assembled small RNAs as a new generation of RNAi therapeutics. Cell Res. 2021;31(6):631-648.

[2]Papi A, Brightling C, Pedersen SE, Reddel HK. Asthma. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):783-800.

[3]Nakayama T, Hirahara K, Onodera A, et al. Th2 Cells in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35:53-84.

[4]Boonpiyathad T, Sözener ZC, Satitsuksanoa P, Akdis CA. Immunologic mechanisms in asthma. Semin Immunol. 2019;46:101333.

[5]Gauvreau GM, Sehmi R, Ambrose CS, Griffiths JM. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: its role and potential as a therapeutic target in asthma. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2020;24(8):777-792.

[6]Tian L, Li W, Wang J, et al. The CKLF1-C19 peptide attenuates allergic lung inflammation by inhibiting CCR3- and CCR4-mediated chemotaxis in a mouse model of asthma [published correction appears in Allergy. 2019 Mar;74(3):639]. Allergy. 2011;66(2):287-297.