Research

Biomarkers are molecules found in bodily serum, fluid, or blood that indicate the presence of a disease or condition. Biomarkers can aid in the understanding of a disease’s progression, cause, and regression in the body (Mayeux, 2004). We selected two breast cancer biomarkers from our preliminary research to use in our detection system: Mammaglobin B and Mucin 1. Mammaglobin B is overexpressed in metastatic breast cancer, and, unlike Mammaglobin A, is found in high levels in various serums aside from breast tissue, such as in the lacrimal and salivary glands (Hassan, 2017). Similarly, circulating high levels of Mucin 1 and amplification of the MUC1 gene has been shown in a significant number of breast cancer cases, and Mucin 1 is found in high levels in sweat gland cells (Kufe, 2013; Kumar et al., 2014). Since both biomarkers are present in sweat and tears, they are effective for a noninvasive method of breast cancer detection. We also selected HER-2 as a positive control; though it is found in blood, it is already established as a breast cancer biomarker with high efficiency.

Figure 1: Uses of biomarkers in disease prognosis, detection, and etiology (Mayeux, 2004).

By detecting biomarkers, a novel and convenient alternative for breast cancer detection can be developed. We first proposed developing or finding a promoter that was induced by our biomarker. Once the promoter was induced, our genetic circuit would then trigger the expression of our reporter, GFP in a host cell. However, research on inducible promoters that are compatible with our biomarkers are scarce, so we decided to abandon this idea due to time and resource constraints.

Instead, we investigated using a cell-free system, and following recommendations from Liu Rengwei, our iGEM mentor, we decided to use aptamers. To detect our selected biomarkers, we chose to utilize aptamers and their partial complementary strands. Aptamers are single-stranded oligonucleotides that bind to target molecules and are developed using SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment). Aptamers bind to targets with high affinity, are easily stored, and can be used for therapeutics, drug delivery, and virus detection, showing that they are effective for precise target molecule detection (Keefe et al., 2010; Zou et al., 2019). We found various aptamers for each of our selected biomarkers and, under recommendation from Professor Ikebukuro, found shorter sequences (<40 bp) and utilized truncated mutants to accurately model the aptamers binding with their target sequences.

We drew inspiration from the past iGEM teams 2018 XMU China and 2016 INSA Lyon. Both teams utilized aptamers and fluorescent-based detection in their systems. XMU China developed a binding assay using the aptamers' complementary strand and CRISPR-Cas 12a as the signal amplifier. After the Cas12a is activated, non specific cleavage occurs, and a fluorescent signal is emitted for detection. INSA Lyon used a sandwich assay where the biomarker was detected via the use of two aptamers. We theorized that using two aptamers would allow for increased specificity and binding, but realized that trying to model a sandwich assay would prove to be difficult due to the lack of proper modeling software. We hope that future teams joining or participating in iGEM can develop a software that allows for efficient modeling of the sandwich assay for aptamers.

Production of Biomarker in an E.Coli System

Since we did not have access to breast cancer cells or cell lines, we decided to have E.Coli synthesize our biomarkers of interest to model the human system. By doing this, we would be able to integrate synthetic biology engineering with our cell-free detection system.

Figure 2: Construct Designs for Parts

We also decided to investigate common parts in the registry such as the T7 and Anderson promoters and their compatibility in synthesizing our biomarkers. Therefore, we decided to design 27 constructs, 9 for each selected biomarker (Mucin 1, Mammaglobin B, and HER2), using a combination of promoters and terminators from the iGEM registry. From the iGEM registry, we selected 3 constitutive promoters: T7 promoter (BBa_I719005), optimized (TA) repeat constitutive promoter (BBa_K137085) and Anderson promoter (BBa_J23100). We also selected 3 terminators: T7 terminator (BBa_K731721), LuxICDABEG terminator (BBa_B0011) and T1 terminator (BBa_B0010). We selected the following promoters and terminators due to their prominence in iGEM experiments and the extensive literature review we performed.

One problem we encountered was that the protein-coding sequence we found via NCBI, was not compatible with the iGEM Biobrick assembly standards. Therefore, as a contribution to future iGEM teams, we made modifications to the protein-coding sequence by inducing silent mutations via the plasmid editing software, ApE.

Figure 3: The grey areas in the figure indicate illegal restriction sites and we resolved this by coding for the same amino acid via a silent mutation using the ApE plasmid editor

We used a combination of PCR, Gibson Assembly, transformation, and purification to synthesize our biomarkers. Further details for our experiment can be found on the Engineering page. When we transitioned to test for the activity between our aptamer and biomarker, we compared the activity of our synthesized biomarkers to biomarkers we ordered from the lab to analyze the quality of our biomarkers and their applicability in a lab setting.

Verification of Aptamer and Biomarker Binding

While the interaction between aptamer and biomarker for some aptamers was reported in literature, we wanted to replicate and verify the findings in our own lab.

Therefore, based on suggestions from NTU Singapore, we decided to use ELISA to verify the interaction between aptamer and biomarker. While ELISA employs the use of antibodies, another method of detection, we used antibodies solely to verify the interaction and did not use antibodies in our final detection assay.

Figure 4: The biotinylated capture antibody is replaced with the biotinylated aptamer for our ELISA assay.

For our ELISA assay, we made use of the interaction between streptavidin and biotin. By coating our plates with streptavidin and using a biotinylated aptamer, when aptamer was added to the 96-well plate, the aptamer would be fixed onto the plate. Therefore, when a biomarker is added to the 96-well plate, the aptamer will bind to the biomarker if there is an interaction between them. This means that when a detection antibody (antibody conjugated to HRP) and TMB is added, if the biomarker successfully binds to the aptamer, the reaction between the TMB substrate and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) will produces a measurable color change.

The measurable color change can be measured by monitoring absorbance using a 96-well plate reader. By plotting a graph of concentration (amount of biomarker used) vs absorbance, and using a non-linear regression with an equation y = (x × Bmax) / (x + Kd), where Bmax is the maximal binding and Kd is the dissociation constant, we will be able to monitor and derive a equation for the activity of our aptamer and its binding affinity.

Aptamer-Based Detection System

AU Nanoparticles Detection

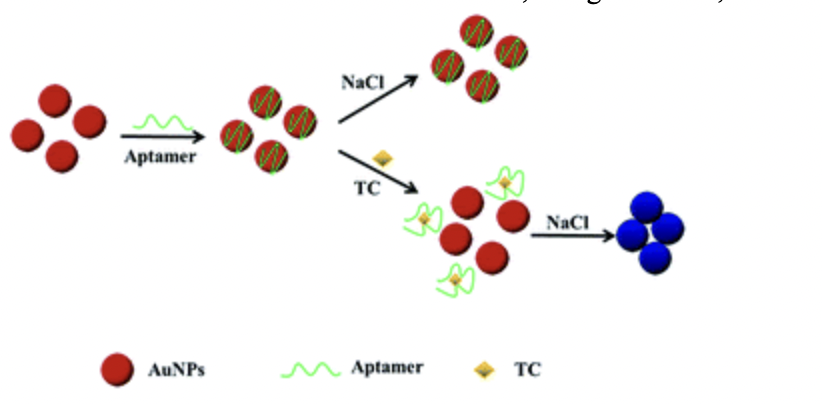

Gold nanoparticles have been versatile in the field of detection. This is commonly seen when excess salt is added to the gold solution, causing the nanoparticle to aggregate. This results in a solution change from red to blue, allowing for colorimetric detection. This detection method is simple, cost-effective, and allows for an easy visualization of the color change, even to the naked eye (Mondal et al., 2018).

We decided to utilize this concept by coating our gold nanoparticles with our aptamer. When our biomarker was added to the aptamer-coated AuNP, the aptamer coupled to the AuNP binds and undergoes a structural change, which causes aggregation and a color shift. When there is an absence of biomarker, the aptamer-coated AuNPs are dispersed and no color change occurs (Bosak et al., 2019). This colorimetric based detection method is clear, straightforward, and user friendly.

Figure 5: When a biomarker is added to conjugated Au-NPs, the Au-NPs undergo a structural change which results in a color shift. (Qi et al., 2018)

Therefore, the utilization of AuNP allows for us to have a colorimetric based biosensor that allows for detection of biomarkers in breast cancer.

Modified Complementary Strand ELISA

Another method for an aptamer-based detection system is to use complementary aptamer strands to function as capture DNA. This makes use of the strand displacement assay, where complementary aptamer strands will be conjugated to the 96-well plate. Then, when aptamer is added to the 96-well plate reader, just like the interaction between streptavidin and biotin, the aptamer will be “captured” by the complementary aptamer strand and fixed onto the plate.

The remainder of the assay is the same as the ELISA assay for the verification of interaction between aptamer and biomarker. Once a biomarker is added to the plate, the biomarker will bind to the aptamer and can be detected by an antibody that is conjugated with HRP, and with addition of the TMB substrate, the reaction will produce a measurable color change.

However, due to the extensive testing needed to select complementary strands and laboratory costs of ordering antibodies and substrates, this assay was not tested by our team this season. However, we provide this as a reference for teams who want to work with aptamer-based detection systems.

XMU China ABCD System

A final method for aptamer-based detection is the Aptamer-Based Cell-free Detection (ABCD) system proposed and developed by the 2018 XMU China team, which was published in the Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology journal this year (Chen et al., 2021).

This system makes use of a complementary strand that is partially complementary to the aptamer sequence. This causes the aptamer to form a double-strand complex with the complementary strand when fixed on a solid phase. This meant that when a biomarker was added, the aptamer would bind to the biomarker and release the “capture” complementary strand.

Figure 6: XMU-China ABCD System

Team XMU China made use of this novel concept by using Cas12a to amplify the signal and DNAse I as the signal reporter to create a novel detection system.

However, the proposed detection system by XMU China requires the measurement of fluorescent intensity, which requires the use of specific detection equipment. We used the XMU China system as an inspiration for our AU nanoparticle assay (where we fixed the aptamer to the nanoparticle) and plan on integrating the use of complementary aptamer strands next year to improve the accuracy and detection of our assay.

References:

- Chen, J., Zhuang, X., Zheng, J., Yang, R., Wu, F., Zhang, A., & Fang, B. (2021). Aptamer-based cell-free detection system to detect target protein. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology, 6(3), 209–215.

- Hassan, E. (2017). In Vitro Selections of Mammaglobin B and Mammaglobin A Aptamers for detecting Metastatic Breast Cancer Cells Using Terahertz Chemical Microscopy [Phd, Université du Québec, Institut national de la recherche scientifique]. http://espace.inrs.ca/id/eprint/8023/

- Keefe, A. D., Pai, S., & Ellington, A. (2010). Aptamers as therapeutics. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 9(7), 537–550.

- Kufe, D. W. (2013). MUC1-C oncoprotein as a target in breast cancer: activation of signaling pathways and therapeutic approaches. Oncogene, 32(9), 1073–1081.

- Kumar, P., Ji, J., Thirkill, T. L., & Douglas, G. C. (2014). MUC1 Is Expressed by Human Skin Fibroblasts and Plays a Role in Cell Adhesion and Migration. BioResearch Open Access, 3(2), 45–52.

- Mayeux, R. (2004). Biomarkers: potential uses and limitations. NeuroRx: The Journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 1(2), 182–188.

- Mondal, B., Ramlal, S., Lavu, P. S., N, B., & Kingston, J. (2018). Highly Sensitive Colorimetric Biosensor for Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B by a Label-Free Aptamer and Gold Nanoparticles. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 179.

- Qi, M., Tu, C., Dai, Y., Wang, W., Wang, A., & Chen, J. (2018). A simple colorimetric analytical assay using gold nanoparticles for specific detection of tetracycline in environmental water samples. Analytical Methods, 10(27), 3402–3407.

- Smith, J. E., Chávez, J. L., Hagen, J. A., & Kelley-Loughnane, N. (2016). Design and Development of Aptamer–Gold Nanoparticle Based Colorimetric Assays for In-the-field Applications. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE, 112. https://doi.org/10.3791/54063

- Zou, X., Wu, J., Gu, J., Shen, L., & Mao, L. (2019). Application of Aptamers in Virus Detection and Antiviral Therapy. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1462.

Figure 6: XMU-China ABCD System

- Chen, J., Zhuang, X., Zheng, J., Yang, R., Wu, F., Zhang, A., & Fang, B. (2021). Aptamer-based cell-free detection system to detect target protein. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology, 6(3), 209–215.

- Hassan, E. (2017). In Vitro Selections of Mammaglobin B and Mammaglobin A Aptamers for detecting Metastatic Breast Cancer Cells Using Terahertz Chemical Microscopy [Phd, Université du Québec, Institut national de la recherche scientifique]. http://espace.inrs.ca/id/eprint/8023/

- Keefe, A. D., Pai, S., & Ellington, A. (2010). Aptamers as therapeutics. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 9(7), 537–550.

- Kufe, D. W. (2013). MUC1-C oncoprotein as a target in breast cancer: activation of signaling pathways and therapeutic approaches. Oncogene, 32(9), 1073–1081.

- Kumar, P., Ji, J., Thirkill, T. L., & Douglas, G. C. (2014). MUC1 Is Expressed by Human Skin Fibroblasts and Plays a Role in Cell Adhesion and Migration. BioResearch Open Access, 3(2), 45–52.

- Mayeux, R. (2004). Biomarkers: potential uses and limitations. NeuroRx: The Journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 1(2), 182–188.

- Mondal, B., Ramlal, S., Lavu, P. S., N, B., & Kingston, J. (2018). Highly Sensitive Colorimetric Biosensor for Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B by a Label-Free Aptamer and Gold Nanoparticles. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 179.

- Qi, M., Tu, C., Dai, Y., Wang, W., Wang, A., & Chen, J. (2018). A simple colorimetric analytical assay using gold nanoparticles for specific detection of tetracycline in environmental water samples. Analytical Methods, 10(27), 3402–3407.

- Smith, J. E., Chávez, J. L., Hagen, J. A., & Kelley-Loughnane, N. (2016). Design and Development of Aptamer–Gold Nanoparticle Based Colorimetric Assays for In-the-field Applications. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE, 112. https://doi.org/10.3791/54063

- Zou, X., Wu, J., Gu, J., Shen, L., & Mao, L. (2019). Application of Aptamers in Virus Detection and Antiviral Therapy. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1462.